EDITOR’S NOTE: Matt is on vacation until at or around January 1, 2026. Until then we have guest posts, today’s post is brought to you by a supply chain expert churner ChooChooTrain. Special thanks for the post!

Introduction

Most churners graduate through three lenses of measuring returns. Only one survives scale.

- Face value: Absolute dollars. No time. No context. Actively misleading once capital grows.

- ROI/APR: Adjusts for capital and time, but collapses the cycle into a single return and ignores reuse.

- Velocity: Measures how fast capital completes cycles and becomes available again.

Velocity matters because churning isn’t a one-shot game. It’s a flow problem.

What matters isn’t the return on a single play, but how capital moves through the system:

- how quickly it comes back,

- whether it can be reused without friction,

- and how many plays (and players) can run in parallel without breaking.

Velocity is how you see whether that flow actually works.

For a deeper treatment of velocity as a system constraint, see MEAB’s Velocity of Money, Part One and Part Two.

Early on, velocity is obvious because monitoring is mandatory. Capital is tight. Timing matters. You know how long money must sit, when it can move, and what breaks if it doesn’t.

As bankroll grows, monitoring quietly shifts from mandatory to optional. Capital spreads wide enough that nothing feels urgent. Timing slack creeps in. Money sits longer than necessary—not because you chose it to, but because nothing forces it to move.

If you’ve been at this long enough, you’ve done all of these:

- “Found” $5k parked in an account you forgot existed

- Missed a bonus because you forgot ten debit swipes on some absurd cadence

- Hit MSR 90 days from card receipt instead of account open and lost the bonus

They feel like one-off mistakes. They’re not. They’re symptoms of systems cushioned by excess inventory.

Core thesis: Your bankroll is inventory. Excess inventory hides problems.

What a Big Bankroll Actually Buys You

Congratulations! You’re rich enough that you can ignore this. Too bad you’re not rich enough that ignoring it doesn’t hurt.

A large bankroll mostly buys comfort: longer payout timelines without better returns, idle capital because it’s easier, messy systems because nothing forces cleanup.

Your bankroll isn’t enabling better plays. It’s subsidizing inattention. Banks appreciate the donation.

What Supply Chain Figured Out Long Ago

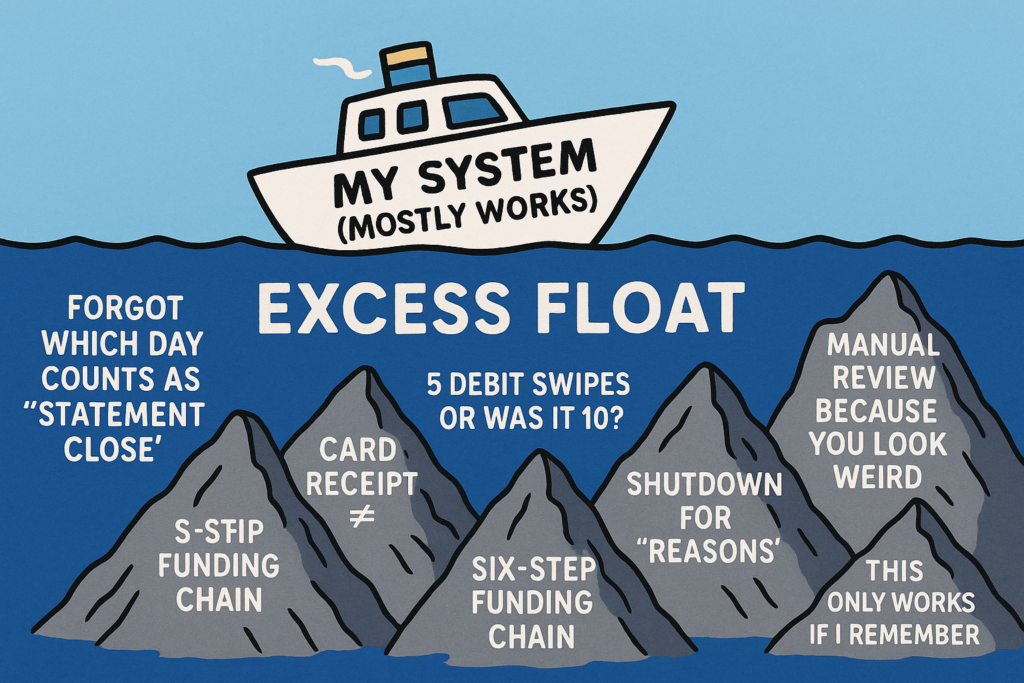

In supply chain 101, there’s a standard illustration: a boat sailing smoothly in high waters.

Below the surface are rocks—bottlenecks, defects, bad processes. As long as the water level (inventory) stays high, the ship sails fine.

Lower the water level and the illusion disappears. The same rocks surface and stop progress. Nothing broke. It was broken the entire time.

A large bankroll does the same thing. Throughput looks fine. Bonuses post. Points flow. But inventory turns lag. Velocity decays quietly.

Fix the System, Not the Symptoms

Kaizen is a manufacturing discipline built around continuous, incremental improvement. Not optimization theater. Not big redesigns. Small fixes, applied relentlessly, with pressure applied.

In manufacturing, you don’t Kaizen by adding inventory. You Kaizen by removing it until the system complains.

If nothing ever feels tight, nothing is getting better. In churning, that “complaint” usually looks like:

- A flow that only works with constant manual babysitting

- Timing failures once even modest variance appears

- Processes that survive solely because float keeps expanding.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re structural warnings.

The Counterintuitive Fix

Improvement starts by lowering the bankroll in play.

Reduce inventory until friction appears. Then treat that friction as a signal, not failure. The goal isn’t to immediately eliminate it, but to understand why it exists.

That analysis often leads to unglamorous fixes:

- Accepting lower headline returns to simplify flows

- Cutting clever edge cases that don’t survive scale

- Finally automating recurring and ad-hoc tasks instead of relying on memory.

The common mistake is reacting by adding capital back in. That doesn’t fix the system. It just quiets it again.

When More Money Is Useful

There are times when increasing bankroll makes sense. The test is simple: does more capital expand what you can capture, or merely prop up how you operate?

- If added capital lets you take a discrete opportunity without altering steady-state flow, your system is likely ready.

- If added capital is required just to keep things moving, it isn’t.

Supply chains solved this long ago. Warehouses aren’t staffed for December in April. Capacity is added briefly for peak demand, then unwound. Ugly. Effective.

Churning’s equivalent is short-term liquidity—HELOCs, margin, similar tools—used deliberately and temporarily. These work only when layered on top of stable flow. Used during system repair, they mask problems instead of solving them. Listen to Kai talk about HELOCs and margin accounts in depth on The Daily Churn Ep 88.

Once extra capital becomes part of steady-state operations, it stops adding flexibility and starts functioning as a crutch.

Increase capacity to handle exceptions, not to subsidize inefficiency.

The End State: Right-Sized, Not Bigger

The goal isn’t a minimal bankroll. It’s a right-sized one.

Right-sized capital reveals problems instead of burying them. It forces timing discipline. It makes velocity visible again.

And it’s not permanent. Issuer behavior changes. Enforcement tightens. Personal capacity shifts. A bankroll that’s right-sized today won’t be tomorrow.

High water feels safe—until it isn’t.

Float conceals. Flow reveals.

– ChooChooTrain

The “ChooChooTrain conjoined rocks of anti-triumph”, now available as a print.